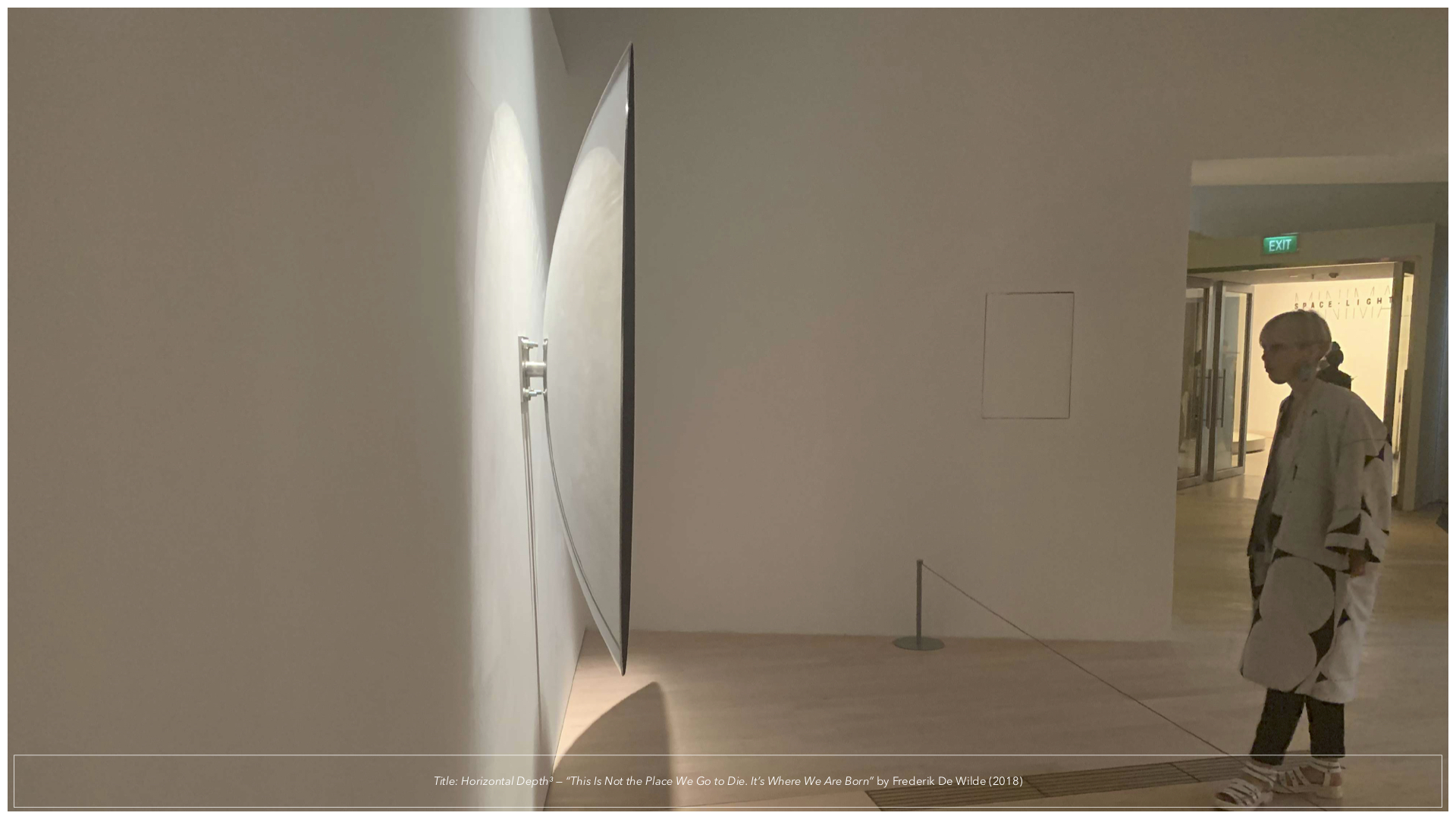

Horizontal Depth³ — “This Is Not the Place We Go to Die. It’s Where We Are Born”

A new iteration of Frederik De Wilde’s blackest black art, Horizontal Depth³, was exhibited in 2018 at the first Minimalism landmark exhibition in Southeast Asia, set across two sites: National Gallery Singapore and ArtScience Museum. Led by National Gallery Singapore, the exhibition features over 150 works that explore the history and legacy of this groundbreaking art movement, which continues to inform a wide range of art forms and practitioners across the world today.

- https://www.nationalgallery.sg/exhibitions/minimalism-space-light-object

Nothingness and the Void are concepts that appear in the Eastern philosophies that influenced Minimalism. Still, they are also essential ideas in science. The vacuum and the void are central features of physics, which have helped shape our understanding of reality. The emptiness that permeates the universe, and the structure of atoms, has long given artists and scientists pause for thought. Whilst quantum mechanics teaches us that empty space in nature is never truly empty, undulating as it is with vacuum fluctuations and invisible quantum fields, it is still extraordinary to ponder the sheer sparsity of the cosmos.

These ideas that bridge philosophy and science fascinated Minimalist artists, inspiring many to find ways of representing the void. Artists today can collaborate with scientists to create work that presents avoid and gives the viewer the closest possible experience of what true ‘nothingness’ might be.

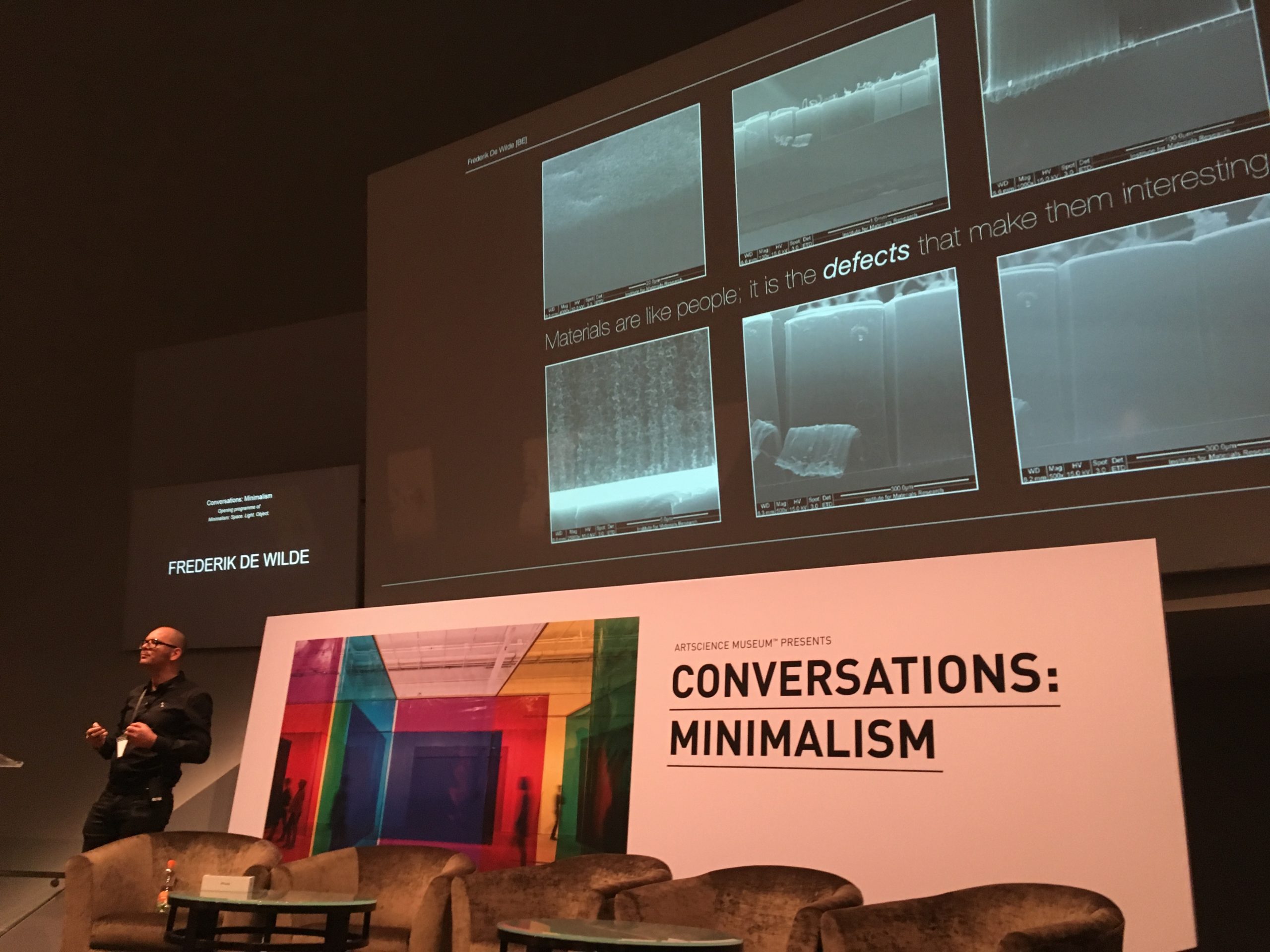

Frederik De Wilde works at the intersection of art, science and technology. In 2010, he engineered a new colour believed to be the blackest black in the world. Working closely with NASA scientists, De Wilde grew his ‘blackest black’ material inside a nanotechnology laboratory. He used it to create several black paintings that directly refer to Russian artist Kazimir Malevich’s iconic 1915 painting, Black Square, widely regarded as one of the most important precursors to Minimalism.

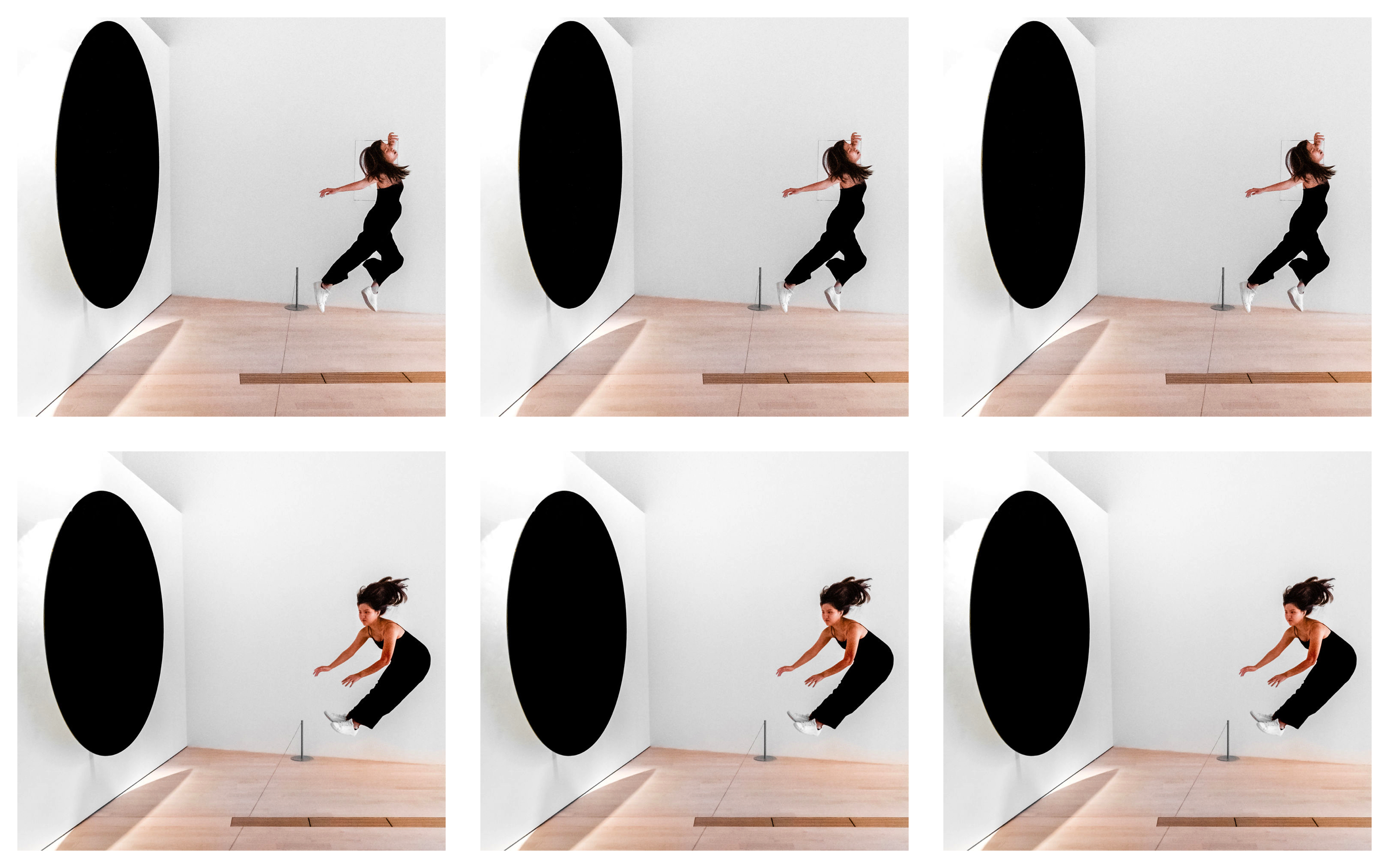

Echoing the circular form of the ensō explored elsewhere in the exhibition and visually evocative of a black hole, this newly commissioned work uses De Wilde’s material to create an encounter with the void, an idea that resonates in Minimalist art, Eastern philosophy and science. The carbon nanotubes used to make the artwork comprise 99.99% air and 0.01% carbon and capture light at all frequencies. When gazing at this artwork, viewers are literally looking into nothing – a void space – and the closest approximation of emptiness that is possible to experience on the Earth.

In the same way that Malevich hoped his Black Square painting would free art of the obligation to depict the real, De Wilde intends his work to open up a space of imagination for the viewer. As the artist notes, “it is the ultimate celebration of the unknown.”

Technical specs Horizontal Depth³ – the original blackest black art

Diameter: 2 meters

Materials: original blackest-black ‘paint’, carbon nanotubes, and stainless steel

Background Horizontal Depth³ – the original blackest black art

Horizontal Depth³ was commissioned by the ArtScience Museum Singapore for the exhibition Minimalism: Space. Light. Object (16 November 2018 to 14 April 2019). The work is currently in a private collection.

Other artists in the exhibition included Anish Kapoor (India), Austin Forbord and Shelley Trott (directors), Carmen Herrera (Cuba), Charwei Tsai (Taiwan), Chen Shiau-Peng (Pescadores Island), Donald Judd (USA), Frederik De Wilde (Belgium), Gerard Byrne (Republic of Ireland), Jeppe Hein (Denmark), Jeremy Sharma (Singapore), Joan Jonas (USA), Mary Miss (USA), Mona Hatoum (Lebanon), Morgan Wong (Hong Kong), Olafur Eliasson (Denmark), Richard Long (UK), Simone Forti (Italy), Song Dong (China), Tan Ping (China), Tawatchai Puntusawasdi (Thailand), teamLab (Japan), Wang Jian (China), Yvonne Rainer (USA), Zhang Yu (China), Zhou Hong Bin (China).

#princealbertfoundation #fpa #blackestblack #vantablack #originalblackestblack #nanotech #carbonnannotubes #blackestpaint #frederikdewilde #anishkapoor #artsciencemuseumsingapore #nationalgallerysingapore #Minimalism #spaceobjectlight #horizontaldepth #nasa #riseuniversity #nanoblack #artscience #black #ultrablack #mit #vantabalck#cnt